A comic-strip diary against a background of war

Comic-strip diaries are rare, although we know of several examples in the Netherlands and abroad. Humour is often a key element. This reflects the comics published in this period, which are particularly remarkable for their adventurous and humorous storylines. In the Netherlands, most comic strips were published in newspapers. Politics was rarely or never explicitly addressed, and disturbing current events usually remained in the background in what were mostly stories aimed at children (although adults regularly read them too). This is true of Lies’ diary and, for example, a magazine such as De Humorist, a supplement to the weekly Panorama, which may have provided the title for the collected notes of Van Gekkum & Co.

Visiting the cartoonist

On a rainy Wednesday morning, we visit the creator of these striking, humorous comics: Lies Bossinade-den Houting. In the backroom of her upstairs flat in Haarlem, next to a roof terrace full of plants, paintings and ceramic figurines, we find her at her dining table. It is full of old photo albums and scrapbooks, and folders containing photocopies of her comic strips. Daughter Anita makes the coffee. Mrs Bossinade, now 95, is in good health, although she says: ‘I only know a lot about the past now, but about recent things? When I see those drawings again, I think: oh yes, that’s what it was like.’

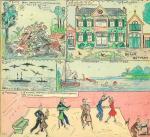

On the eve of the Second World War, she lived with her father, mother and little sister on Vijverhofstraat in Rotterdam, above her grandma and grandpa. On the afternoon of Tuesday, 14 May 1940, the house was destroyed when the Germans bombed the city. Homeless but unharmed, her grandparents moved in with the young family, who had moved to Schieweg. Mrs Bossinade has never forgotten the wartime bombing raids. ‘You’d hear a strange hum in the distance’, she recalls. ‘That was the bombers coming. We lived in an upstairs apartment with a staircase; then we’d go and sit under the stairs with coats over our heads. It was such a dreadful sound.’

The Duo of Van Gekkum & Co.

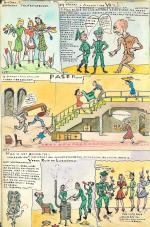

Lies and her best friend Rita, who was also from Rotterdam, called themselves the ‘Duo of Van Gekkum & Co.’ ‘I was Van Gekkum and Ria was Co’, says Mrs Bossinade. At school, where they invariably sat next to each other, they were equally troublesome. In one short comic strip, Lies is sent out of the classroom. In the toilet next to the class, she continues to act up: ‘I’m tapping on the toilet window, the whole class was in stitches’, she says. ‘Miss Groen was spitting fire. She really couldn’t stand me. I was always larking about.’ When the bombing forced the Den Houting family to move in 1942, Lies wrote (referring to herself in the third person as usual): ‘This is where the Rotterdam part ends, because Van Gekkum & Co. are splitting up. Lies is going to live in Zoeterwoude. Ria will live here until June, whereupon she too will move, to Enschede.’ Lies sometimes hitched a lift to see her friend in Twente: ‘Van Gekkum had a good old chat from 11 in the evening until 5 in the morning. Then a game of skipping.’

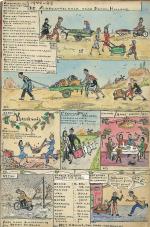

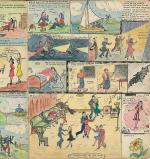

Despite all the drastic events of the war, friendship, entertainment and free time were important aspects of her childhood during the occupation. The search for relief thus forms an essential part of her dairy entries, in which daily life is usually viewed and depicted with humour. But drawings of food-scavenging trips (‘hongertochten’) also feature in the diary. Under the title ‘The potato race to Noord Holland’, they give a striking picture of the worrying situation. She was confronted with raids and shelling, which also ended up in the diary. This gives her story a raw edge, although – remarkably – it hardly detracts from the cheerful tone.

A passion for drawing

In 1944, she turned eighteen – ‘what a crazy feeling, knowing you’d never be turned away from the cinema ever again’ – passed her school exams, and began domestic science school. But her passion was for drawing. That passion had developed years beforehand, with her grandfather on Vijverhofstraat. ‘Grandpa was a “shoe artist”: he made beautiful shoes for elderly people with difficult feet. He would sit in the attic with a large box of coloured pencils, drawing models. He would cut each pencil in two, sharpen it and give one half to me.’

There was no lack of examples. She read about the adventures of Tom Poes in De Telegraaf, for instance. She also loved science fiction: ‘Flash Gordon was a hero. I was crazy about him!’ Mrs Bossinade showed us a collection of translated comics that she kept. ‘The crazier the adventure, the more I loved it. And that’s still the case now, in my old age.’

A number of events are not shown in the diary. For example, she had an uncle and aunt with National Socialist sympathies, and she therefore broke contact with them. The arrest of her uncle, who would eventually die in Neuengamme, does not feature in her diary, either.

Nor is the persecution of the Jews reflected in the drawings. ‘I was friends with a Jewish girl. We were in the same class. Cohen, Loulou Cohen’, says Mrs Bossinade, when, after some effort, the girl’s name comes to mind. Like Lies, the Cohen family lived on Schieweg in Rotterdam. ‘She was with another Jewish girl. They never came back,’ she recalls. ‘When we were doing homework at school, she was always secretly copying mine. That used to annoy me quite a bit.’ At a certain point her friend disappeared, presumably after she was forced to attend a Jewish school after the summer holidays of 1941. ‘She was taken away and never came back.’

The misery of the war situation does not seem to have been deliberately filtered out of this unique diary. But the urge to survive, nevertheless to make something of an individual existence that was not constantly defined by various limitations and a lack of freedom, the urge to experience some happiness as a growing teen, often outweighs the tendency to portray the developments of the war and their impact on wider society. As a result, the turmoil of war is pushed into the background, as it were, making room for an unexpectedly cheerful voice.

The diary was continued after the liberation. It ends in 1952, with an announcement of the birth of her first son, Bastiaan. Now that the comic-strip diary is available at NIOD, it deserves a wider readership