Luck, wisdom and infrastructure. On an unexpected historical source and a helpful colleague.

Last week, the postman delivered a new book full of recent research findings based on known and unknown comic strips from popular culture; comic strips about the Holocaust. Amongst the contributions by various authors is an article entitled: ‘The Invisible Jews in August Froehlich’s “Nazi Death Parade” (1944). An Early American Sequential Narrative Attempt to Visualize the Final Stages of the Holocaust.’ Marking as it does the (preliminary) completion of research, a new publication always feels like a reward, but as working on this specific project piqued my curiosity more than usual, unwrapping it was a genuine pleasure.

The hefty volume is called Beyond MAUS. The title refers to the famous comic strip by Art Spiegelman, the American author who, since the 1980s, has made it clear to an ever-growing audience of readers and critics that comic strips can offer a nuanced, poignant picture of the Holocaust. Thanks to sequential narratives such as these, the comic strip is recognised as a medium with depth and great creative potential that can also captivate adult readers. The word ‘beyond’ in the title underlines the focus on other comics about the persecution of the Jews.

In recent years, more and more comic strips around the world have depicted the impact and scope of the Holocaust. An increasing number of readers have seen this genocide visualised not only in exhibitions, documentaries and feature films, but also in graphic novels about Anne Frank and other victims. In the flourishing international comic market, the offering on this historic topic is substantial, but also relatively easy to survey. What is more complicated is to track down comics that were not published as separate books. After all, comics also appear in magazines and newspapers, brochures and other printed matter.

Identifying an early comic-strip interpretation

As expressions of popular culture, many of these latter variants are not preserved in libraries and archives, meaning that they are not described or otherwise made accessible. This makes it difficult to identify them, something that is especially true of relatively early comic-strip interpretations of the traumatic history of the Holocaust. Before Spiegelman broke through with Maus, generations of readers had already come across the Holocaust through the drawn cartoon, particularly through accounts that were not reprinted and thus not available to successive generations of readers. Such comics could nevertheless have an impact, especially at a time when little attention was being paid to the fate of Europe’s Jews under National Socialism.

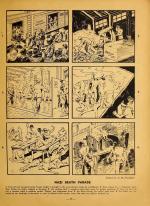

Three years ago, I came across a small image on the Internet when I – as I often did – simply typed ‘comic’ and ‘holocaust’ into Google Images. This basic search sometimes produced results that differed from the previous one. Indeed, after some scrolling I spotted a small but intriguing black-and-white image. A photo of yellowed paper with drawings in six small frames, including a scene from a gas chamber. Was I seeing the final phase of the Holocaust depicted in cartoon form? The version on the website showing the image was hardly any bigger, but I was nevertheless able to discover the title of the original publication. It turned out to have been published in the US before the German capitulation. I could hardly believe what I was seeing. We know of some early American comics from the 1940s that showed concentration camps with sadistic Nazis and their victims. They tended to be stereotypical-looking free interpretations; Jewish victims were shown sporadically, at most. During the war, artists did not usually indicate that they were aware of the actual Endlösung in any detail. The unique thing about this short comic strip was that it did seem to point to information from eyewitnesses.

The Bloody record and a helpful librarian

But how could I get hold of that publication, so I could meticulously study the short comic strip in context? Besides being scarce, the unusually rare antiquarian copies turned out to be very expensive, and no copies were available in Europe. Only a few libraries in the US, Canada and Israel had a copy of the pamphlet, called The bloody record of Nazi atrocities. Coincidentally, my colleague Marjo Bakker, a subject specialist at NIOD, was working as an EHRI fellow at the library of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC at the time. As she explained in her prompt reply to my impatient email, it turned out that they had digitised the publication. I was delighted with the energetic and peerless performance of the library staff on both sides of the Atlantic.

Although the front page of the publication was missing, I was now able to consult the other fifty pages digitally – presumably one of the first readers to do so this century. This searing pamphlet, published barely a year before the end of the war to impress upon American adults the infamy of the Nazi regime – and thereby justify American military deployment – featured numerous illustrations. They included a single page by August Froehlich, a relatively obscure cartoonist of Central European origin. As early as 1944, before the liberation of Auschwitz, he wanted to create a concise visual account of what was increasingly rumoured in the free world to be happening, but was usually considered impossible. A comic artist, of all people, was one of the first publicly to depict the unimaginable.

I was impressed by this find, and the more I delved into it, the more intriguing this comic – a neutral-looking but remarkably selective representation in a clearly politicised context – became. Who was the artist? What were his sources of information and what considerations did he make? Who were the other authors of this publication? What impact did the cartoon have, and why did it eventually fall into obscurity? In 2019, I had the opportunity to share my first answers with a select audience at a conference in Austria. And now, two years on, a detailed analysis has appeared in Beyond Maus: The Legacy of Holocaust Comics, which will soon be available in the NIOD library. A book full of contributions that could only have come about with the support and interest of colleagues near and far. It thus brings luck, wisdom and infrastructure together in fruitful fashion.

Ole Frahm, Hans-Joachim Hahn and Markus Streb (eds), Beyond MAUS: The Legacy of Holocaust Comics (Vienna: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2021)